How to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, unlock $1 trillion of land, and free 1 billion days of time

Congress and the Biden Administration are in discussions on a multi-trillion dollar infrastructure bill. Much of that money would fund construction of roadways using concrete, steel, and asphalt.

For our climate, let’s pause on this one. Let’s start by funding challenge prizes for the three best flying car produced in the next year. Give the world twelve months and then award a first-place prize of $1 billion, a second place prize of $750 million, and a third place prize of $250 million. Have minimum parameters for the entries, something like (a) must fly 15 miles in 15 minutes, (b) vertical take off and landing, (c) electric or gasoline engine at equal or lower emissions than four-door sedan, and (d) noise limited to some reasonable magnitue. This would be a inducement prize contest in the great historical tradition.

Flying cars could not only decrease greenhouse gas emissions, but could save billions of hours of time commuting and free up trillions of dollars of urban land. To see how we can free up 9 New York Cities of urban land in the United States, read on.

For the climate

Flying cars would combat climate change. You already know that gasoline engines contribute somewhere around one quarter of global CO2 emissions. But production of concrete, cement, iron, and steel contribute another 12-14%, and growing.

In other words, infrastructure spending on traditional concrete and asphalt roads is a greenhouse gas behemoth. What can we do to lessen that impact?

Flying cars would need far less concrete, asphalt, and steel to support transport routes. Imagine not needing to build and maintain so many surface streets and freeways. You need a place to take off and a place to land. The sky is your roadway.

Flying cars also expand routes in a third dimension so that we don’t all need to cluster onto the same two-dimensional roads. This means less congestion, fewer stop signs, and fewer traffic lights.

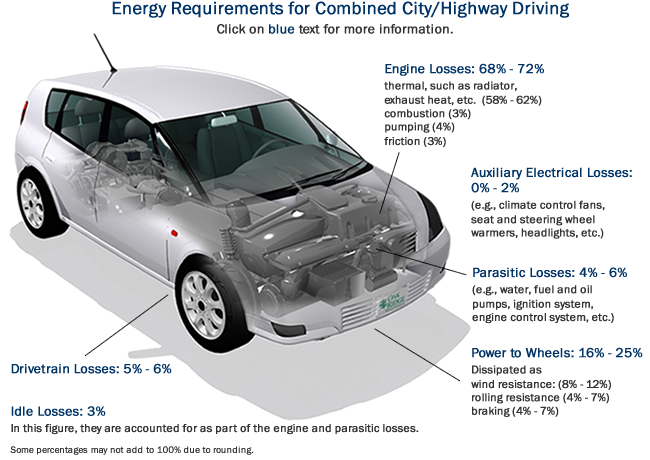

Reducing congestion and stop-and-go driving through this third dimension would decrease energy use. Below is a figure of energy use in gasoline vehicles. Because of the physics of the internal combustion engine, only 16-25% of the gasoline’s energy powers the wheels. In typical use, half of that 16-25% is used to overcome rolling resistance (friction with the roadway) and in braking (stop-and-go).

Traveling in a flying car rather than via two-dimensional roadways allows avoiding congestion, stop signs, and traffic lights and could mean point-to-point transit so less total distance traveled. All these factors would notably cut energy costs in transit. Takeoff for flying vehicles is doubtless costly in energy. My hunch, though, is that this is outweighed by the energy savings of point-to-point.

Cutting our commute and growing our cities

Benefits to flying cars extend well beyond infrastructure costs and climate change. Imagine the benefits to commute times and land use.

In 2019, 148 million Americans commuted to work at an average round-trip duration of 55.2 minutes. That is 221 hours of commuting per worker per year or more than 1.3 billion 24-hour days spent commuting by American workers. In a single year. Imagine the time and potential unlocked by cutting this number even by 10 percent, let alone in half or more.

Flying cars would save us space in addition to time. I estimate that public roadways take up 5,600 square miles – more than 6 percent – of Federal Urbanized Areas in the United States. To give you a sense of scale, New York City covers 302.6 square miles. Sprawling Houston covers 669.

Roadways use massive amounts of highly valuable real estate.

Here is my calculation: In 2019, the United States had an estimated 8.8 million lane-miles of public roadways with 2.8 million in Federal Urbanized Areas – densely settled core geographies of at least 50,000 people.

The American Road & Transportation Builders Association estimates that every 1,000 lane-miles covers about two square miles of area. Combining this estimate with the DOT numbers suggests public roadways use about 5,600 square miles of Urbanized Areas. This is 6.3 percent of the Federal Urbanized Area total surface area of 88,500 square miles.

Imagine what we could do if we reclaimed half of that land. These 2,800 square miles would be the equivalent of 9 New York Cities. And this land is some of the most valuable on earth. If urban land in America was worth $500,000 per acre in 2010 and has since increased in value by 50 percent, these 2,800 square miles of urban roadways cover around $1.3 trillion of land. Even with downward price pressure from increased supply, it’s hard to imagine the land would be less productive for our economy than concrete. Imagine the housing supply or greenspace that might be built.

Further reading

The Kindle eBook Where’s My Flying Car? by J. Storrs Hall prompted some of these ideas. The book is fascinating if a little preachy. Hall’s history of the death of the flying car industry is devasting as to the stultifying effects of air travel regulations. For a short review of the book, check out Roots of Progress.

The payoff

$1 trillion in urban land value, another $1 trillion in avoided infrastructure costs, 1 billion work-days of commuting, and a non-trivial decrease in the transportation and construction vectors that currently generate 40% of CO2 emissions.

The ask

My $2 billion ask is a penance compared to multi-trillion dollar economic benefits, life satisfaction from a reduction in commute times, and reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

Let’s aim big. Combat climate change. Improve our lives. Grow our economies.

Challenge prizes for flying cars, please.